Structural Placement: Where Doolittle's Work Fits Among Social Science Movements

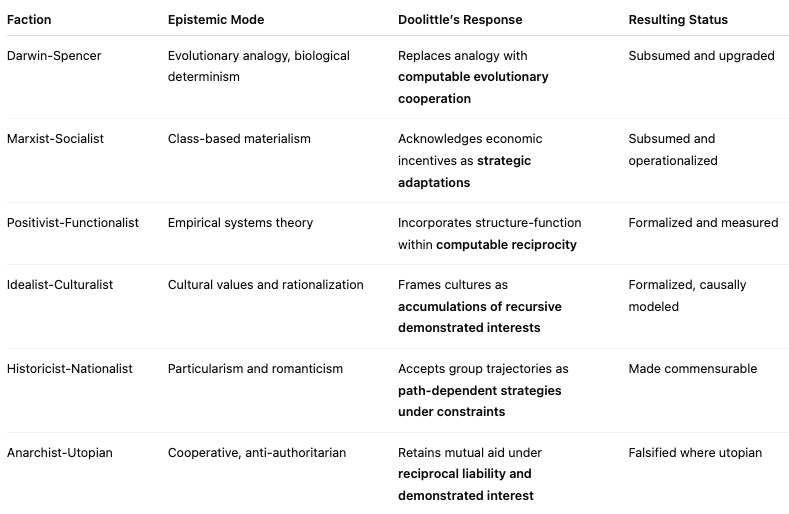

Curt Doolittle’s Natural Law framework does not belong within any of the traditional 19th–20th century intellectual factions (e.g., Darwin-Spencer, Marxist, Positivist). Rather, it represents a successor paradigm—a comprehensive epistemological and legal reconstruction that subsumes, falsifies, and reconstructs those prior schools under a new standard of operational, decidable, and reciprocal measurement.

Doolittle’s system could be classified as a Computable-Reconstructionist School, characterized not by ideology, but by the construction of a universal grammar of decidability, testimonial truth, and demonstrated interests, capable of analyzing any institutional, economic, or moral system in terms of evolutionary computation and reciprocity.

Refining Doolittle’s Methodology with Demonstrated Interests and Classical Liberalism

Curt Doolittle’s methodology, as developed through the Natural Law Institute, is a rigorously operational framework rooted in classical liberalism, specifically a Hayekian or Jeffersonian variant that constrains government through the natural, common, concurrent law of sovereignty in demonstrated interests and reciprocity in display, word, and deed. This methodology fundamentally posits that all behavioral and social phenomena are reducible to statements of demonstrated interests, moving beyond the narrow and misleading framing of “property” used in libertarian and propertarian discourses. Unlike Rothbardian libertarianism, which Doolittle critiques as unethical and immoral for evading the costs of commons and enabling predatory behavior under the guise of individual sovereignty, his framework is ethically grounded in the preservation of commons as a source of polity discounts, ensured through reciprocal defense of demonstrated interests. The methodology unifies the following components to analyze assertions and social systems with empirical and moral rigor:

Epistemology: Constructs objective knowledge from first principles (e.g., identity, succession, reciprocity), reducing phenomena to statements of demonstrated interests—actions, preferences, or commitments individuals reveal through behavior. This ensures claims are measurable and free from speculative or biased constructs.

Causal Testifiability: Validates claims through explicit constructions (proofs or counterexamples) across testable dimensions (e.g., consistency, correspondence, reciprocity), using hierarchical checklists to isolate networks of demonstrated interests and their outcomes, ensuring empirical precision.

Sovereignty-Reciprocity: Defines sovereignty as an individual’s right to act within the limits of reciprocal cooperation, where reciprocity prevents parasitism and preserves the commons’ discounts (e.g., trust, infrastructure). Unlike libertarianism’s commons-evading ethic, this principle enforces mutual liability through natural law, aligning individual and collective interests ethically.

Decidability: Determines whether a claim or system is true, false, or undecidable using limits-based reasoning, achieving certainty through computational logic and operational clarity, ensuring disputes over demonstrated interests are resolved objectively.

Limits-Based Reasoning and Full Accounting Between Limits: Employs constructive logic to define assertion boundaries, requiring a balance-sheet accounting of short-, medium-, long-term, and evolutionary consequences on total capital (material, social, cultural, biological). This prevents selective reasoning by capturing all impacts on a population’s adaptive capacity, avoiding biases like adaptive resistance to change or conflation of experiential (subjective) goods with consequential (objective) goods. It ensures ethical evaluation free from arbitrary judgments.

This methodology externalizes cognitive processes into operational checklists, compensating for human biases and ensuring reproducibility. By reducing phenomena to demonstrated interests, it rejects Rothbardian libertarianism’s separatist ethic, which Doolittle critiques for enabling seduction into hazard and institutionalizing criminality against the commons.

Instead, it aligns with the Germanic-Anglo-American moral tradition of reciprocal defense, positioning Doolittle as a classical liberal who advances Jeffersonian ideals with greater empirical rigor and less naïve optimism.

Functional Comparison: Relation to Other Factions

Historical Context

These factions emerged during a period of rapid industrialization, imperialism, and scientific advancement (late 18th to early 20th centuries). Each sought to explain social change in response to these transformations, often competing for intellectual dominance.

1. Darwin-Spencer Wing

Core Ideas: Natural selection, survival of the fittest, laissez-faire individualism, social evolution.

Explanation: The Darwin-Spencer wing applied biological principles of natural selection and survival of the fittest to social organization, emphasizing competition as a driver of progress. Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory and Herbert Spencer’s social philosophy argued that societies evolve from simple to complex forms through individual competition and adaptation, with laissez-faire individualism promoting minimal state interference. This framework viewed social evolution as a natural process, prioritizing efficiency and merit over artificial interventions, though often ignoring cultural and institutional complexities.

Relevance: The faction’s historical significance and alignment with Doolittle’s universalism justify its inclusion, but its failures highlight the need for nuanced applications.

Key Figures: Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, William Graham Sumner. Charles Darwin (1809–1882) Contribution: Developed the theory of evolution by natural selection (outlined in On the Origin of Species, 1859). His work emphasized adaptation, survival, and reproduction as drivers of biological change. Influence: Provided the scientific foundation for applying evolutionary principles to human societies, though Darwin himself was cautious about such extensions. Relevance: His ideas inspired social scientists to explore "survival of the fittest" in social contexts, though often misapplied. Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) Contribution: Coined the phrase "survival of the fittest" and developed a comprehensive philosophy applying evolutionary principles to sociology, ethics, and politics (Social Statics, 1851; Principles of Sociology, 1876–1896). Advocated laissez-faire individualism, believing societies evolve from simple to complex forms. Influence: Popularized Social Darwinism, arguing that competition and natural selection drive social progress, often justifying inequality and imperialism. Relevance: Spencer’s work shaped early sociology and social theory, though his deterministic views later faced criticism. William Graham Sumner (1840–1910) Contribution: American sociologist and Social Darwinist (Folkways, 1906). Argued that social customs and institutions evolve through competition and adaptation, opposing government intervention in social processes. Influence: Applied Spencerian ideas to American sociology, defending individualism and free-market capitalism. Relevance: His work reflects the Darwin-Spencer emphasis on natural social evolution, though often used to justify social hierarchies. Francis Galton (1822–1911) Contribution: Darwin’s cousin; pioneered eugenics and statistical approaches to heredity (Hereditary Genius, 1869). Explored how natural selection could be artificially directed to "improve" human populations. Influence: Extended Darwinian principles to human traits, influencing early genetics and social policy, though eugenics later became controversial. Relevance: Represents the application of Darwinian ideas to social engineering, aligning with Spencer’s optimism about progress. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) Contribution: Economist and demographer (An Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798). Argued that population growth outpaces resources, leading to competition and struggle. Influence: Influenced Darwin’s concept of natural selection and Spencer’s views on societal competition. Relevance: His ideas prefigured the Darwin-Spencer focus on struggle as a driver of change, applied to both biology and society.

Criticisms/Failures: Ethical Misapplication: Social Darwinism, rooted in Spencer’s ideas, was widely criticized for justifying imperialism, racism, and economic inequality by framing them as “natural” outcomes of competition. This led to its rejection in mainstream social science by the mid-20th century. Oversimplification: The biological analogy of evolution was criticized for ignoring cultural, institutional, and historical factors, as noted by Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, who argued social systems are more complex than natural selection models suggest. Determinism: Spencer’s belief in inevitable progress was faulted for underestimating human agency and the role of deliberate social reform, contributing to its decline as deterministic views fell out of favor.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s work aligns with this wing’s universalist natural law and emergent orders but avoids biological determinism by grounding propertarianism in causal testifiability. His epistemological rigor could address oversimplification critiques, though his libertarianism risks being seen as justifying inequality, echoing Social Darwinism’s ethical issues.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s classical liberal methodology retains the Darwin-Spencer insight into evolutionary dynamics, reducing competition to statements of demonstrated interests via epistemology. Causal testifiability measures cooperative outcomes across dimensions (e.g., resource allocation), while limits-based reasoning evaluates short-, medium-, long-term, and evolutionary impacts on total capital, preventing selective reasoning that justifies inequality. Full accounting ensures all consequences (e.g., social trust) are captured, countering ethical misapplications. Sovereignty-reciprocity enforces mutual liability through natural law, rejecting laissez-faire’s commons-evading tendencies. Decidability resolves disputes about evolutionary fitness empirically. For example, Doolittle’s model analyzes market competition through checklists of reciprocal interests, ensuring ethical cooperation preserves commons discounts.

Advancement: By grounding evolutionary principles in testable, reciprocal frameworks, Doolittle mitigates the faction’s ethical and deterministic failures.

2. Marxist and Socialist Wing

Core Ideas: Class struggle, historical materialism, economic determinism, socialism.

Explanation: The Marxist-Socialist wing emphasized class struggle, economic determinism, and the role of material conditions in shaping society. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that history progresses through conflicts between classes (e.g., bourgeoisie vs. proletariat), driven by economic structures, culminating in a classless, socialist society. Historical materialism framed social change as rooted in production relations, rejecting biological or cultural determinism in favor of economic forces, with socialism as the solution to capitalist exploitation.

Relevance: This wing dominated socialist and communist movements, influencing 20th-century political ideologies and social sciences.

Key Figures: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Ferdinand Lassalle. Karl Marx (1818–1883): Developed historical materialism; argued that capitalism’s internal contradictions would lead to revolution (The Communist Manifesto, 1848; Das Kapital, 1867). Friedrich Engels (1820–1895): Collaborated with Marx; applied Marxist ideas to social institutions like the family (The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, 1884). Ferdinand Lassalle (1825–1864): German socialist who influenced early labor movements, focusing on state-driven reforms.

Criticisms/Failures: Economic Reductionism: Critics like Weber argued Marxism overemphasized economic factors, neglecting cultural, religious, and ideological influences on social change. Failed Predictions: Marx’s prediction of inevitable proletarian revolution did not materialize in advanced capitalist societies, where reforms and welfare states mitigated class conflict, as noted by scholars like Ralf Dahrendorf. Authoritarian Outcomes: Marxist-inspired regimes (e.g., Soviet Union) led to authoritarianism and economic stagnation, undermining claims of emancipatory potential, a critique raised by anarchists like Mikhail Bakunin.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s libertarian propertarianism opposes Marxism’s collectivism, but both address economic systems. His causal testifiability could critique Marxism’s reductionism, offering empirical rigor to analyze social dynamics without deterministic assumptions.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle preserves Marxism’s awareness of stratified incentives and capital accumulation, acknowledging how resource disparities shape social dynamics. However, he applies operational measures of parasitism and capital type (e.g., productive vs. extractive capital), rejecting economic reductionism. His framework analyzes incentives through causal testifiability, identifying parasitic behaviors empirically rather than assuming class-based inevitability. This counters Marxism’s authoritarian tendencies by prioritizing voluntary, property-based cooperation over collectivist mandates.

Advancement: Doolittle’s approach addresses reductionism and failed predictions by offering a nuanced, testable analysis of incentives, aligning with his anti-statist principles while retaining Marxist insights into power dynamics.

Inclusion Rationale: Marxism’s influence on social theory and politics warrants inclusion, but its failures underscore challenges Doolittle avoids through individualism.

Contrast with Darwin-Spencer: Marxists rejected the Darwin-Spencer emphasis on individual competition and natural selection, viewing society as shaped by collective class dynamics rather than biological analogies. While Darwin and Spencer saw progress as inevitable through competition, Marxists saw it as contingent on revolutionary change.

3. Positivist and Functionalist Wing

Core Ideas: Scientific sociology, social cohesion, functional interdependence, empirical universalism.

Explanation: The Positivist-Functionalist wing sought to establish sociology as a science, focusing on social cohesion and the functional interdependence of societal institutions. Auguste Comte and Émile Durkheim argued that societies operate like organisms, with institutions serving specific functions to maintain stability. Empirical universalism aimed to uncover general social laws through observation, prioritizing measurable data over speculative theories, though often at the cost of individual agency and conflict dynamics.

Relevance: Laid the foundation for modern sociology, emphasizing scientific rigor and social stability over biological determinism.

Key Figures: Auguste Comte (1798–1857): Founder of positivism; proposed a "science of society" (sociology) to uncover laws of social progress (Course of Positive Philosophy, 1830–1842). Émile Durkheim (1858–1917): French sociologist; emphasized social facts and collective consciousness (The Division of Labor in Society, 1893; Suicide, 1897). Viewed society as held together by shared norms, not competition. Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923): Italian sociologist; analyzed social equilibrium and elites, blending positivist and evolutionary ideas.

Criticisms/Failures: Conservatism: Functionalism was criticized for justifying the status quo by framing social institutions as inherently stabilizing, ignoring conflict and inequality, as argued by C. Wright Mills. Neglect of Agency: Its focus on social systems over individuals was faulted by interpretive sociologists like Weber, who emphasized human agency and meaning. Overambition: Comte’s positivism was criticized for its grandiose aim to predict social laws universally, often lacking empirical specificity, as later sociologists like Robert Merton noted.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s causal testifiability shares positivism’s scientific rigor, but his individualism counters functionalism’s collectivism. His work could address agency critiques by grounding social orders in voluntary, property-based interactions.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle utilizes the functional dependencies between institutions highlighted by Durkheim, recognizing the systemic nature of social order. However, he replaces normativity with measurable outcomes, using causal testifiability to assess institutional efficacy rather than assuming their stabilizing role. This addresses conservatism by evaluating institutions based on their contribution to reciprocal cooperation, not their maintenance of tradition. His focus on individual agency through demonstrated interests counters the faction’s neglect of human initiative.

Advancement: By grounding functional analysis in empirical outcomes and individual agency, Doolittle overcomes the faction’s conservative bias and overambitious universalism, aligning with his scientific classical liberalism.

Contrast with Darwin-Spencer: While the Darwin-Spencer wing used biological evolution as a model for social progress, positivists and functionalists focused on empirical observation and social integration. Durkheim criticized Spencer’s individualism, arguing that society is more than the sum of individual competitions.

4. Idealist and Culturalist Wing

Core Ideas: Core Ideas: Cultural meaning, human agency, rationalization, historical contingency.

Explanation: The Idealist-Culturalist wing emphasized the role of cultural meaning, human agency, and rationalization in shaping social behavior. Max Weber and others argued that values, beliefs, and historical contexts drive social change, with rationalization (e.g., bureaucratic systems) shaping modern societies. Unlike deterministic models, this faction highlighted contingency and subjective interpretation, viewing societies as products of human action rather than universal laws, though risking relativism.

Relevance: The faction’s foundational role in sociology justifies inclusion, but its failures highlight limitations Doolittle’s approach mitigates through epistemological focus. Influenced cultural sociology, anthropology, and historical studies, offering a counterpoint to biological and economic determinism.

Key Figures: Max Weber (1864–1920): German sociologist; argued that cultural factors, like the Protestant work ethic, shaped economic behavior (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 1905). Emphasized rationalization and bureaucracy. Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911): German philosopher; advocated for understanding human sciences through lived experience and historical context, opposing positivist universalism. Georg Simmel (1858–1918): German sociologist; explored social interactions and cultural forms, focusing on individuality within modern societies.

Criticisms/Failures: Relativism: The emphasis on cultural specificity was criticized for risking relativism, making it hard to derive universal principles, as structuralists like Claude Lévi-Strauss argued. Limited Predictive Power: Weber’s focus on historical contingency was faulted for lacking predictive models, unlike positivism or Marxism, limiting its practical application. Elitism: Some critics, like those in critical theory, argued Weber’s focus on rationalization and bureaucracy implicitly favored Western modernity, sidelining non-Western perspectives.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s epistemology engages rational systems, but his universalist natural law contrasts with cultural relativism. His causal testifiability could counter relativism critiques by grounding cultural insights in empirical tests. Doolittle’s epistemology reduces cultural values to demonstrated interests, while causal testifiability measures their impact across dimensions like cooperation. Limits-based reasoning evaluates intertemporal impacts on total capital (e.g., cultural cohesion), countering relativism with universal reciprocity. Full accounting prevents selective focus on subjective goods, ensuring objective analysis. Sovereignty-reciprocity locates agency within natural law, rejecting libertarian commons-evasion. Decidability resolves cultural disputes empirically. For instance, Doolittle’s model analyzes religious values through checklists of reciprocal interests, ensuring ethical, bias-free outcomes.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s influence on cultural sociology warrants inclusion, but its failures highlight tensions with Doolittle’s universalism.

Contrast with Darwin-Spencer: This wing prioritized cultural and subjective factors over the Darwin-Spencer focus on universal laws of competition and survival. Weber, for instance, critiqued simplistic evolutionary models, emphasizing the complexity of human motives and institutions.

5. Historicist and Nationalist Wing

Core Ideas: Focused on the unique historical development of nations or cultures, often tied to romanticism or nationalism. Historicists argued that societies evolve through distinct, context-specific paths, rejecting universal evolutionary laws.

Key Figures: Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803): German philosopher; emphasized cultural uniqueness and the "spirit" of each nation, influencing nationalist thought. Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886): German historian; advocated for studying history "as it actually happened," focusing on particular events and national histories. Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896): German historian; linked historicism to nationalism, glorifying state power and cultural identity.

Criticisms/Failures: Nationalist Excesses: Historicist nationalism was criticized for fueling aggressive imperialism and ethnocentrism, notably in 20th-century conflicts, as postcolonial scholars like Edward Said noted. Anti-Universalism: Its rejection of universal laws limited its theoretical scope, clashing with scientific sociology’s aims, as Durkheim argued. Romantic Bias: The romanticized view of national “spirit” was faulted for lacking empirical rigor, criticized by positivists for speculative history.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s universalism rejects historicist particularism, though his organizational insights (e.g., group dynamics) share some concerns. His causal testifiability counters romantic bias with empirical grounding.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle acknowledges the historicist emphasis on group-based identities (e.g., family, clan, nation) as organizational dimensions, as seen in his prior discussions of social structures. However, he re-situates these within a universal framework of reciprocal contractual liability, using causal testifiability to measure their cooperative efficacy rather than romanticizing their uniqueness. This counters nationalist excesses and anti-universalism by subordinating group dynamics to objective principles of natural law.

Advancement: Doolittle’s universalist, empirical approach mitigates romantic bias and nationalist pitfalls, integrating group dynamics into his propertarian system.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s historical role in shaping nationalism justifies inclusion, but its failures highlight why Doolittle’s universalist approach diverges.

Contrast with Darwin-Spencer: Historicists rejected the universal evolutionary framework of Darwin and Spencer, emphasizing particularity over general laws. They viewed social change as driven by cultural or national spirit rather than biological or competitive mechanisms.

Relevance: Shaped historical studies and nationalist ideologies, particularly in Europe, but often clashed with scientific approaches to social theory.

6. Anarchist and Utopian Wing

Core Ideas: Advocated for decentralized, egalitarian societies, rejecting both capitalist competition and state authority. Anarchists and utopians envisioned social progress through cooperation and communal organization, often critiquing industrial hierarchies.

Key Figures: Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876): Russian anarchist; opposed centralized authority and advocated for collective action (Statism and Anarchy, 1873). Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921): Russian anarchist; argued that mutual aid, not competition, drives evolution and social progress (Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, 1902). William Morris (1834–1896): British socialist; envisioned utopian, cooperative societies inspired by pre-industrial ideals.

Criticisms/Failures: Impracticality: Anarchism was criticized for lacking viable mechanisms to govern complex societies, as Marxists like Engels argued, leading to its marginalization. Naïve Optimism: Kropotkin’s mutual aid was faulted for overestimating human cooperation, ignoring conflict, as realists like Pareto noted. Limited Impact: Anarchist movements struggled to achieve lasting institutional change, often overshadowed by Marxist or reformist strategies.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle’s anti-statism and emergent orders align with anarchism, but his propertarianism contrasts with its anti-capitalism. His causal testifiability could address impracticality by providing rigorous frameworks for decentralized systems.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle acknowledges Kropotkin’s mutual aid as an emergent strategy, aligning with his libertarian anti-statism. However, he constrains it within reciprocal contractual liability, ensuring cooperation is enforceable through property-based legal structures. His causal testifiability measures mutual aid’s outcomes, addressing naïve optimism by identifying conditions for sustainable cooperation. This counters impracticality by providing a structured framework for decentralized systems.

Advancement: Doolittle’s rigorous, property-based approach overcomes the faction’s impracticality, enhancing its anti-statist insights with practical mechanisms.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s anti-authoritarian legacy warrants inclusion, and its failures highlight challenges Doolittle’s structured libertarianism aims to overcome.

Contrast with Darwin-Spencer: Anarchists like Kropotkin directly challenged the Darwin-Spencer emphasis on competition, arguing that cooperation and mutual aid are central to human and animal evolution. They rejected Spencer’s laissez-faire individualism as justifying exploitation.

Relevance: Influenced libertarian socialism and modern cooperative movements, offering an alternative to both capitalist and Marxist frameworks.

Recent Factions

7. New Social Movement Theory (NSM)

Core Ideas: Identity, post-materialism, decentralized cultural change.

Key Figures: Alain Touraine, Alberto Melucci, Ronald Inglehart, Steven Buechler.

Criticisms/Failures: Elitism: NSM’s focus on middle-class, post-material concerns was criticized for sidelining working-class or Global South issues, as Marxist scholars like Ellen Meiksins Wood argued. Fragmentation: Its emphasis on diverse identities risked diluting collective action, lacking the unifying power of class-based movements, per critics like Craig Calhoun. Overemphasis on Culture: Critics argued NSM neglected structural economic factors, limiting its explanatory power for global inequalities, as noted in postcolonial critiques.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: NSM’s decentralized networks align with Doolittle’s libertarianism, but its identity focus challenges his universalism. His causal testifiability could critique NSM’s cultural bias, grounding it empirically.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle incorporates NSM’s insight into decentralized networks and identity-driven cooperation, recognizing their role in post-industrial societies. However, he re-situates these within a computable system of reciprocity, using causal testifiability to measure how identity-based movements contribute to cooperative outcomes. This addresses elitism by applying universal principles to all groups, not just the middle class, and counters fragmentation by prioritizing enforceable property rights over diffuse cultural goals. His framework mitigates the overemphasis on culture by grounding social change in measurable incentives.

Advancement: Doolittle’s universalist, empirical approach overcomes NSM’s elitism and fragmentation, integrating its network insights into his libertarian framework.

Inclusion Rationale: NSM’s shift to cultural paradigms justifies inclusion, but its failures suggest Doolittle’s universalist approach may offer broader applicability.

8. Postmodernist-Post-Structuralist Wing

Core Ideas: Fragmented narratives, power-knowledge, deconstruction.

Key Figures: Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, Judith Butler.

Criticisms/Failures: Relativism: Postmodernism’s rejection of universal truth was criticized for undermining normative claims, as Jürgen Habermas argued, risking intellectual nihilism. Obscurantism: Its dense, jargon-heavy style was faulted for alienating practical applications, per critics like Noam Chomsky. Limited Political Impact: Its focus on discourse over material action limited its ability to effect systemic change, as Marxist critics noted.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Postmodernism’s relativism clashes with Doolittle’s objective epistemology. His causal testifiability could counter obscurantism, offering clear, testable principles.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle engages postmodernism’s critique of knowledge production, recognizing power dynamics in narrative construction. However, he counters relativism by anchoring knowledge in causal testifiability, ensuring claims are empirically verifiable. His clear, operational definitions (e.g., property, reciprocity) address obscurantism, replacing jargon with testable principles. While postmodernism’s focus on discourse limits political impact, Doolittle’s propertarianism translates power insights into actionable legal frameworks.

Advancement: Doolittle’s rigorous epistemology mitigates relativism and obscurantism, integrating power-knowledge insights into his objective natural law system.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s influence on philosophy and cultural studies warrants inclusion, but its failures highlight why Doolittle’s rigorous approach diverges.

9. Postcolonial-Decolonial Wing

Core Ideas: Non-Western epistemologies, anti-Eurocentrism, colonial critique.

Key Figures: Edward Said, Homi K. Bhabha, Walter Mignolo, Aníbal Quijano.

Criticisms/Failures: Overgeneralization: Critics like Arif Dirlik argued postcolonial theory sometimes homogenized the Global South, ignoring local diversity. Academic Insulation: Its focus on academic discourse was faulted for limited practical impact on decolonization, as activists like Frantz Fanon’s legacy suggests. Tensions with Universalism: Its rejection of Western frameworks risked dismissing useful tools (e.g., scientific methods), as some development scholars noted.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Postcolonial anti-universalism conflicts with Doolittle’s natural law, but his agency focus resonates with decolonial autonomy. Engaging postcolonial critiques could broaden his work’s global scope.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle incorporates postcolonial critiques of Eurocentric universalism, testing his natural law’s applicability across diverse cultural contexts. He uses causal testifiability to measure cooperative outcomes in non-Western settings, addressing overgeneralization by grounding analyses in specific, empirical data. His framework counters academic insulation by proposing practical, property-based legal structures for global application. While postcolonial theory rejects universalism, Doolittle re-situates its insights within a reciprocal, universal framework, ensuring cultural diversity informs but does not override objective principles.

Advancement: Doolittle’s empirical, universalist approach mitigates overgeneralization and insulation, enhancing postcolonial insights with practical applicability.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s global impact justifies inclusion, but its failures suggest Doolittle’s universalism could complement its insights with rigor.

10. Critical Theory-Neo-Marxist Wing

Core Ideas: Cultural hegemony, emancipatory critique, power dynamics.

Key Figures: Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Jürgen Habermas, Nancy Fraser.

Criticisms/Failures: Pessimism: The Frankfurt School’s focus on cultural domination was criticized for lacking actionable solutions, as per critics like Perry Anderson. Elitism: Its academic focus was faulted for disconnecting from grassroots movements, unlike classical Marxism. Overemphasis on Culture: Neglecting economic structures limited its explanatory power, as post-Marxists like Laclau and Mouffe acknowledged.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: Critical theory’s anti-capitalism opposes Doolittle’s propertarianism, but shared rational inquiry suggests dialogue. His causal testifiability could counter pessimism with empirical solutions.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle preserves critical theory’s focus on cultural hegemony and power dynamics, analyzing how institutions shape incentives. However, he replaces pessimism with causal testifiability, measuring power’s impact on cooperation empirically. His propertarianism counters elitism by empowering individual agency through property rights, accessible to all. While critical theory overemphasizes culture, Doolittle balances this with economic and legal analyses, ensuring a holistic approach to social dynamics.

Advancement: Doolittle’s optimistic, inclusive framework mitigates pessimism and elitism, integrating power insights into his reciprocal system.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s evolution of Marxism warrants inclusion, but its failures highlight Doolittle’s practical, individualist approach.

11. Social Movement Theory (Resource Mobilization and Framing)

Core Ideas: Resource mobilization, framing, collective action.

Key Figures: John McCarthy, Mayer Zald, David Snow, Charles Tilly.

Criticisms/Failures: Over-Rationalization: Its focus on strategic action was criticized for ignoring emotional or spontaneous aspects of movements, as cultural sociologists like James Jasper argued. Western Bias: Postcolonial scholars noted its models often fail to explain Global South movements, which rely on different resources and contexts. Neglect of Power: Its organizational focus sometimes sidelined structural power dynamics, as critical theorists critiqued.

Relation to Doolittle’s Work: The faction’s organizational focus aligns with Doolittle’s emergent orders, and his epistemology could enhance its empirical rigor. His universalism could address Western bias by testing principles globally.

Integration in Doolittle’s Work: Doolittle incorporates social movement theory’s insights into strategic coordination and narrative construction, recognizing their role in mobilizing cooperation. He uses causal testifiability to measure resource mobilization’s efficacy and framing’s impact on reciprocal outcomes, addressing over-rationalization by accounting for emotional and cultural factors. His universalist framework counters Western bias by testing principles globally, while his focus on property rights addresses power dynamics neglected by the faction. This ensures movements align with enforceable, cooperative structures.

Advancement: Doolittle’s empirical, universal approach mitigates biases and enhances power analyses, integrating strategic insights into his propertarian system.

Inclusion Rationale: The faction’s strategic focus justifies inclusion, and its failures suggest Doolittle’s causal testifiability could strengthen its frameworks.

Distinctives of Doolittle’s Framework

1. Methodological Shift:

Replaces narrative justification with operational demonstration

Supplants ideological preference with causal necessity

Treats institutions not as ideals, but as computable constraints on cooperation

2. Claims to Authority:

Not grounded in analogy (Spencer), prophecy (Marx), tradition (Herder), empiricism (Comte), or moral vision (Kropotkin)

Grounded instead in evolutionary constraints, existential scarcity, and human cognitive limits, operationalized through testimonial truth individual sovereignty and reciprocity

3. Tests of Validity:

Not popularity, coherence, or narrative

But truthfulness (testifiability), reciprocity in demonstrated interests, and resistance to parasitism

Integration: Bridge to Prior Factions

Doolittle’s Natural Law does not reject historical theories wholesale. Instead, it extracts their testable components and re-situates them within a computable system of cooperation. For instance:

From Darwin-Spencer: Retains evolutionary dynamics, but embeds them in multiscale, moralized computation constrained by reciprocity

From Marx: Preserves awareness of stratified incentives and capital accumulation, but applies operational measures of parasitism and capital type

From Durkheim: Utilizes functional dependencies between institutions but replaces normativity with measurable outcomes

From Weber: Incorporates rationalization and values, but locates them within the hierarchy of actions driven by demonstrated interests

From Kropotkin: Acknowledges mutual aid, but only as an emergent strategy within reciprocal contractual liability

Conclusion: What Doolittle’s Natural Law Consists of

Doolittle’s system is not one among many ideological theories—it is a paradigm shift that renders them commensurable, decidable, and measurable. Where historical factions isolated specific causal dimensions (e.g., biological, economic, cultural), Doolittle reconstructs them as dimensions of evolutionary computation within a universal system of cooperative constraint.

In this view, the previous wings of thought are rendered not obsolete, but components of a higher-order system: useful only insofar as they survive tests of truth, reciprocity, and computability.